Many comics over the last few years have embraced a lighter, Silver Age style as a reaction to the latest age of grim’n’gritty, or at least to present an amusing sideshow attraction. Al Ewing and Brendan McCarthy’s The Zaucer of Zilk (a 2000 A.D./Rebellion import, courtesy of IDW) recreates the aesthetic as a reaction to this neo-Silver movement. It’s less reassuring, less protective, and less nostalgic than its American mainstream peers, and more probing into our own motives.

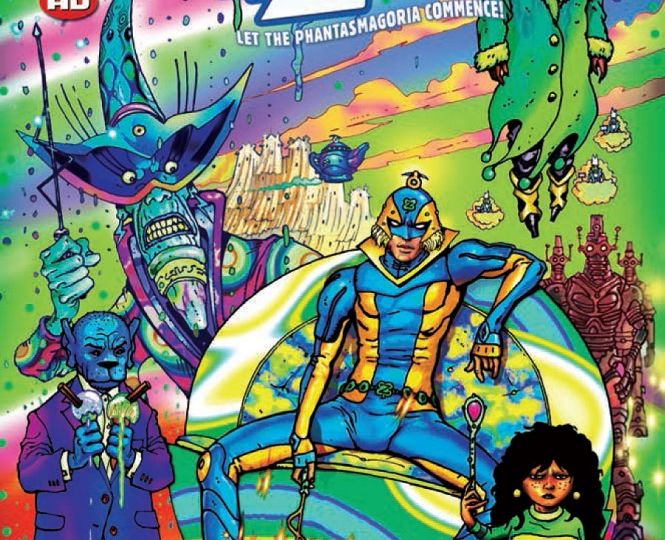

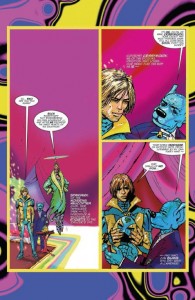

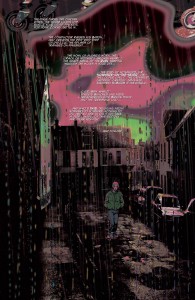

McCarthy and colorist Len O’Grady practically beg comparison between Mike and Laura Allred, as well as Frank Quitely (but lacking his polish), with garish coloring and just slightly off renderings from what is usually considered “beautiful.” Zaucer of Zilk is filled with psychedelic backgrounds–your usual swirls of color, the occasional near-subliminal image, that sort of thing. A talking dog-man sidekick, and other cartoon holdovers from comics’ yesteryear adorn the pages set in the world of the comic’s magic-based hero, Zaucer. This candy-coated wonderland, Zilk, conflicts with “Dankendreer,” one of the dimensions of mediocrity created by the villainous Errol Raine. If Raine isn’t devoted to evil for its own sake, he’s at least devoted to trapping people in mundane existences of endless drizzle, sports matches where no one ever wins, and everyone walking around with hope removed from their eyes. While Dankendreer represents all the horrors of everyday life, Zilk is the escapism so many fans seek. It’s where the quiet, unpopular boy can be well-loved by millions, where problems are solved with the wave of a wand, and where great men put on special pants both feet at the same time just because they are better. It’s precisely everything that’s presumably wanted from a super-book. If this is starting to sound like a Steve Gerber comic, well, that comparison might not be far off, particularly with many of the collages where the narrator (who actually becomes involved in the plot) soliloquizes about the nature of the two dimensions.

McCarthy and colorist Len O’Grady practically beg comparison between Mike and Laura Allred, as well as Frank Quitely (but lacking his polish), with garish coloring and just slightly off renderings from what is usually considered “beautiful.” Zaucer of Zilk is filled with psychedelic backgrounds–your usual swirls of color, the occasional near-subliminal image, that sort of thing. A talking dog-man sidekick, and other cartoon holdovers from comics’ yesteryear adorn the pages set in the world of the comic’s magic-based hero, Zaucer. This candy-coated wonderland, Zilk, conflicts with “Dankendreer,” one of the dimensions of mediocrity created by the villainous Errol Raine. If Raine isn’t devoted to evil for its own sake, he’s at least devoted to trapping people in mundane existences of endless drizzle, sports matches where no one ever wins, and everyone walking around with hope removed from their eyes. While Dankendreer represents all the horrors of everyday life, Zilk is the escapism so many fans seek. It’s where the quiet, unpopular boy can be well-loved by millions, where problems are solved with the wave of a wand, and where great men put on special pants both feet at the same time just because they are better. It’s precisely everything that’s presumably wanted from a super-book. If this is starting to sound like a Steve Gerber comic, well, that comparison might not be far off, particularly with many of the collages where the narrator (who actually becomes involved in the plot) soliloquizes about the nature of the two dimensions.

Like with Gerber, there’s a running satirical theme to Zaucer of Zilk, though here it’s less devoted to the big, existential issues so much as the comic industry and fandom’s unwillingness to engage them. Ewing’s prose is not a playful elbow to the ribs, but a punch in the face. The narrator frequently comments about how the readers don’t want to spend any time thinking about Dankendreer (“…We can take a peek at it whenever we like. But why would we want to?”), teasing how we use art to avoid thinking by asking, “Let’s have some fun, eh?” Further, it paints the plucky young Zaucer as an arrogant ass, condescending to two loyal companions (even after they rescue him from Raine) and a fan, the text-speaking Tutu, whom he allows to tag along “until she starts boring [him].” This, in spite of his powers being directly related to how much his fans adore him, but he never seems in short supply of such love (a touch of celebrity worship to go along with industry criticism). While Ewing and McCarthy do place Zaucer on a redemption arc, such a stipulation insinuates that any good he does perform will always be self-serving objectivism rather than genuine empathy or concern.

Like with Gerber, there’s a running satirical theme to Zaucer of Zilk, though here it’s less devoted to the big, existential issues so much as the comic industry and fandom’s unwillingness to engage them. Ewing’s prose is not a playful elbow to the ribs, but a punch in the face. The narrator frequently comments about how the readers don’t want to spend any time thinking about Dankendreer (“…We can take a peek at it whenever we like. But why would we want to?”), teasing how we use art to avoid thinking by asking, “Let’s have some fun, eh?” Further, it paints the plucky young Zaucer as an arrogant ass, condescending to two loyal companions (even after they rescue him from Raine) and a fan, the text-speaking Tutu, whom he allows to tag along “until she starts boring [him].” This, in spite of his powers being directly related to how much his fans adore him, but he never seems in short supply of such love (a touch of celebrity worship to go along with industry criticism). While Ewing and McCarthy do place Zaucer on a redemption arc, such a stipulation insinuates that any good he does perform will always be self-serving objectivism rather than genuine empathy or concern.

Zaucer of Zilk is a good companion piece to Ewing’s skewering of vigilantism in Jennifer Blood, the Dynamite title he inherited from provocateur Garth Ennis. Where Blood hits hard the grim power fantasies the Big Two lately revelled in, Zaucer picks at the underlying nostalgia within titles like Wolverine and the X-Men or Amazing Spider-Man. What lies underneath is even more Dankendreer.

It’s never too late to check out a quality title like The Zaucer of Zilk!