As much as The Crow is a revenge fantasy, it is also about pain, anger, and love. Not just Eric’s romance with Shelly, or the relationship between him and the gang he hunts, but also with himself; with God; with the city of Detroit; and with music. James O’Barr’s grief poem resonates on far more levels than its premise implies, because it isn’t about the revenge. Not really.

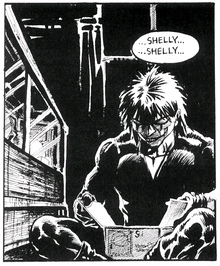

Much of the series is taken up with Eric (who wouldn’t get the surname “Draven” until the movie) reminiscing or cutting himself. Memory, emotion, and hallucination colliding into a personal hell. The titular crow chastises Eric for this (“Don’t Look!”), but he can’t help it. As The Crow progresses, these side trips down memory lane overtake the plot. Eric visits with a little girl, Sherri, and contacts a police captain, Hook. The gritty Detroit streets (shades of Frank Miller) give way to mixed media depictions of Eric and Shelly’s past. O’Barr uses paintings and graphite along with his usual pencils to lend a dreamy, Gothic vibe to his pages. What O’Barr is bringing to The Crow is the sensibility of Poe. Like Poe’s writings, The Crow hinges on powerful, often macabre images: a horse tangled in barbed wire, cats on a stairway, even Eric’s facepaint (based on comedy and tragedy masks). Also like Poe, O’Barr brings a songwriter’s ear to his prose, especially in his chapter introductions (“So the Crow spirals down through a collapsed dream/And the only sound he makes is a concave scream”).

Much of the series is taken up with Eric (who wouldn’t get the surname “Draven” until the movie) reminiscing or cutting himself. Memory, emotion, and hallucination colliding into a personal hell. The titular crow chastises Eric for this (“Don’t Look!”), but he can’t help it. As The Crow progresses, these side trips down memory lane overtake the plot. Eric visits with a little girl, Sherri, and contacts a police captain, Hook. The gritty Detroit streets (shades of Frank Miller) give way to mixed media depictions of Eric and Shelly’s past. O’Barr uses paintings and graphite along with his usual pencils to lend a dreamy, Gothic vibe to his pages. What O’Barr is bringing to The Crow is the sensibility of Poe. Like Poe’s writings, The Crow hinges on powerful, often macabre images: a horse tangled in barbed wire, cats on a stairway, even Eric’s facepaint (based on comedy and tragedy masks). Also like Poe, O’Barr brings a songwriter’s ear to his prose, especially in his chapter introductions (“So the Crow spirals down through a collapsed dream/And the only sound he makes is a concave scream”).

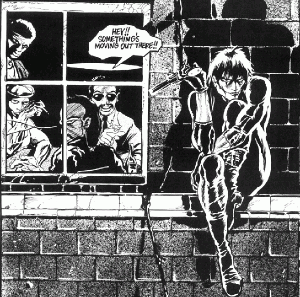

Music seems to play an important part in The Crow. Lyrics and references to various punk bands abound (the Cure and Joy Division, especially). Eric’s body language is inspired by Iggy Pop, graceful yet aggressive. It becomes an engaging performance to watch Eric appear before his enemies, terrorizing and confusing them. Alex Proyas would translate this into the movie’s music video aesthetic.

Where Proyas and O’Barr differ is their emphasis on violence. The movie had a much flashier, action flick look to Eric’s revenge; O’Barr is just blunt. Point blank shots, stabbings, one man bleeding out from being hacked off at the ankles; death is never pretty with O’Barr’s pencils. In fact, The Crow becomes much less interested in dispatching its bloodthirsty freaks as the intervening scenes become longer. They also become more painful, as Eric eventually recalls the night he and Shelly were murdered. Rather than bringing catharsis, each kill leaves sorrow. By the end of the series, Eric is sitting against a tombstone. All he can do is recall a conversation with Shelly. Three panels highlight his eyes, a gun in the snow, and a praying statue, and he concludes, “It’s forever now,” referring to death. There’s an emotional honesty to this ending–where no amount of violence alleviates suffering–that’s missing from The Crow‘s grim’n’gritty contemporaries.

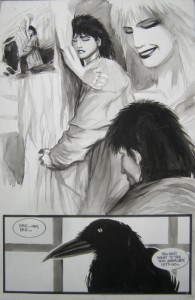

O’Barr himself related a similar journey (The Crow was a reaction to the death of his fiance), saying, “it made me more self-destructive, if anything. There is pure anger on each page, little murders.” Where other artists of the dark age of comics were drawing violence as escapism, O’Barr’s approach has more self-awareness. The use of women as symbols, as causes to take up the gun in the typical super-book/revenge fantasy had more than a little sexism to it. While O’Barr’s pages share that (Shelly and Sherri often appear angelic, idealized, another form of objectification), that doing so only brings further torment remains important to the text.

O’Barr himself related a similar journey (The Crow was a reaction to the death of his fiance), saying, “it made me more self-destructive, if anything. There is pure anger on each page, little murders.” Where other artists of the dark age of comics were drawing violence as escapism, O’Barr’s approach has more self-awareness. The use of women as symbols, as causes to take up the gun in the typical super-book/revenge fantasy had more than a little sexism to it. While O’Barr’s pages share that (Shelly and Sherri often appear angelic, idealized, another form of objectification), that doing so only brings further torment remains important to the text.

Ironically, the retribution against each of the rapists/killers become far more personal the less they are the center of The Crow. In the beginning, Eric shoots, slices, or stabs them with efficiency, just checking off a list. However, when he gets to Fun Boy (the second to last on the list), Eric let’s him go warn the last (T-Bird). Later, before actually killing Fun Boy, Eric has a conversation with him about their views of self. The scene ties together many running themes, including man’s relationship with the metaphysical (“We do not recognize our souls until they are in pain.”) and absolutism (Eric and Fun Boy being love and destruction). The fight scene against T-Bird that follows is genre convention, but this exchange is The Crow’s true climax. Where victim and criminal empathize, rather than hate. Their pain, while different, is still pain. The grim reality of The Crow is that the only other thing to cling to is love.

What did you think of the book? Would you say that it is a must read?

I believe it's an absolute necessity that you read The Crow if you consider yourself a fan of comics. The fact that you know how much real pain has gone into the creation is one of the most profound things about this publication.

I've never fallen to the depths of hate and despair that is dripping off every page. Hopefully, I never will. But it's a journey that is compelling, haunting and beautiful all at once. Great article by the way. Thanks.